David Lewis

Research

You can find my publication list here

Current research

The H2O-NH3 binary system at planetary interior conditions

The "Ice Giants", Uranus and Neptune, are the two most distant planets in the Solar System. Current theory suggests that their interiors are rich in planetary ices such as water, ammonia, hydrogen sulphide, and methane. Understanding the propeties of these materials at the extreme conditions (high pressure, high temperature) found inside planets is cruicial to explain observations of the ice giants, such as the magnetic field and gravitational moments.

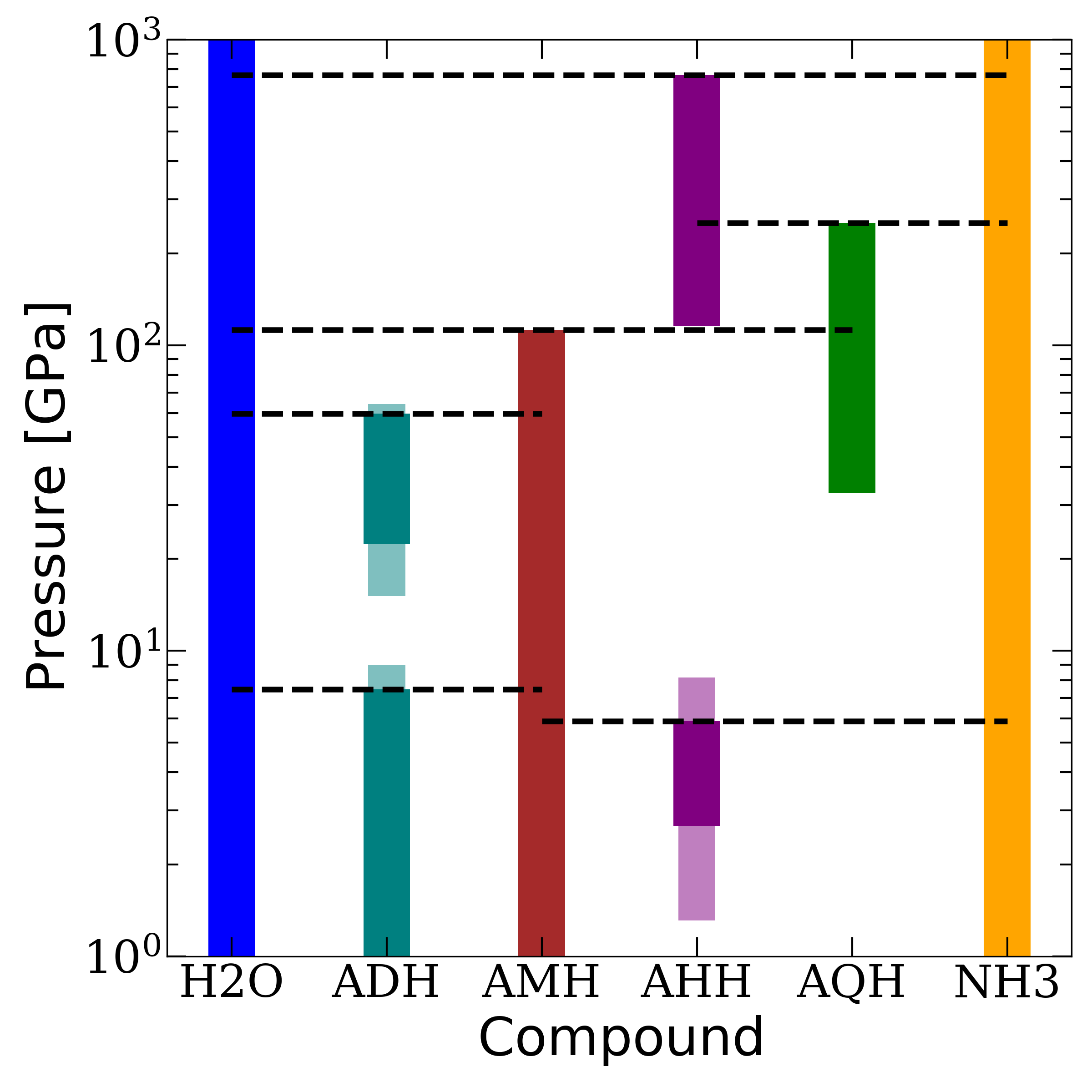

I am currently invesitgating the behaviour of mixtures of water and ammonia at planetary interior conditions from first principles using density functional theory (DFT). When mixed, water and ammonia form a series of compounds known collectively as the ammonia hydrates, (H2O)x(NH3)y.

At ambient conditions there are three ammonia hydrates with different stoichiometries which can exist: ammonia monohydrate (AMH, NH3:H2O), ammonia dihydrate (ADH, NH3:2 H2O), and ammonia hemihydrate (AHH, 2 NH3:H2O). Ammonia quarterhydrate (AQH, 4 NH3:H2O) has been predicted to be stable at high pressures using ab intio structure searching methods.

In my current work, I am calculating absolute Gibbs free energies for the various high pressure states which arise in water, ammonia, and the ammonia hydrates. The ultimate goal is to build a binary phase diagram at planetary interior conditions and construct miscibility realtions. These relations will help us to understand how mixtures of water and ammonia influence the interiors of ice giants, in particular with regard to de-mixing and possible stratification.

Previous research

My previous research has focused on the study of exoplanet and solar system planet atmospheres. In particular, I have worked to gain a better understand of the expected propties of the clouds which form in these diverse chemical environments. Below is a short summary of a key result from Helling, Samra, Lewis et al. (2023), and more of my work can be found in Helling, Lewis, Samra et al. (2021).

Global trends in micro-physical cloud properties

The population of currently known exoplanets covers a wide thermochemical regime. Cloud formation is expected to occur in the atmospheres of most gas-giant exoplanets. The composition and spatial distribution of these clouds depends on the local thermodynamic conditions in the atmosphere. In my previous work, I have studied how the micro-physical properties of clouds vary across the atmospheres of hot and ultra-hot Jupiter exoplanets.

Cool, Transition, and Hot Exoplanet Atmospheres

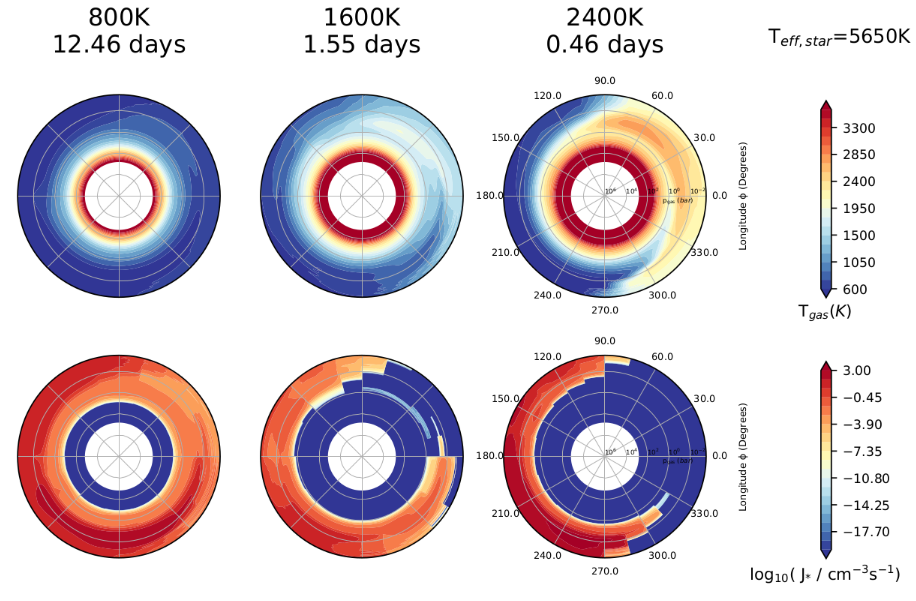

In Helling, Samra, Lewis et al. (2023), we applied a hierarchical modelling approach of post-processing the 1D kinetic cloud formation model DRIFT/StaticWeather (Woitke & Helling (2004), Helling & Woitke (2006)) on to a grid of cloud-free 3D General Circulation Models (GCMs) for hot Jupiters. This grid of GCMs (Baeyens et al. (2021)) spans a wide global parameter space of planetary equilibrium temperaure (Teq = 400 - 2600 K) and multiple stellar types (M, K, G, and F). We identify three classes of gas-giant atmospheres based on their cloud properties:

- Class (i): Cool atmospheres (Teq ≤ 1200 K)

- Homogeneous nucleation rate and global cloud coverage

- Class (ii): Transition atmospheres (Teq = 1400 − 1800 K)

- Patchy nucleation rate and partial cloud coverage

- Class (iii): Hot atmospheres (Teq ≥ 2000 K)

- Nightside localised nucleation and cloud coverage